There have been several attempts in recent years to regionalize tasks and specific homeless system response efforts in the Twin Cities Metro Region. Each effort has resulted in strategies and solutions to respond to homeless crises and sometimes reduce the harm experienced by people experiencing homelessness. This effort aims to advance systemic strategies that unearth the rooted and historical racial inequities in the region that are leaving local entities feeling perpetually behind in their efforts collectively.

The Heading Home Minnesota Funders Collaborative (HHMFC) contracted with the National Innovation Service (NIS) Center for Housing Justice (CHJ) to build upon past efforts at regionalization, and create an approach to cross-jurisdictional efforts that has the potential to transform local efforts toward a regional system that builds toward housing justice.

The Blueprint for regionalization is:

- a reflection of major structural themes that frequently surfaced across a diverse set of community members and stakeholders in the Twin Cities Metro Region working to prevent and end homelessness;

- a proposed set of actions that can begin to address structural barriers to preventing and ending homelessness in the region, many of which are rooted in racism; and

- a roadmap to creating a different kind of regional planning and decision-making table, one that is rooted in justice.

To understand what it means to advance regionalization built on racial equity and housing justice requires an understanding of the origin of policies and practices that already exist in those spaces. Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) have historically experienced housing instability and homelessness at significantly greater rates than their white counterparts. This disproportionality is the result of systemic racism and histories of white supremacist policy enacted to deprive BIPOC communities of access to resources and wealth-building mechanisms—including homeownership. While experiencing homelessness, (in addition to the trauma suffered through the experience of homelessness) institutional and systemic racism from within the homeless response system, especially its services, results in harmful and negative outcomes.

In A Brief Timeline of Race and Homelessness in America, the National Innovation Service and our partners in the National Racial Equity Working Group outline the historical connections between race and homelessness in the United States, including a timeline that illuminates the origin of policies and practices that drive homeless response systems today. A system built on racial equity and housing justice must be able to identify and translate historical and present-day racist trauma into policy, practice, and action that both redresses previous harm and moves toward a new reality.

For the Twin Cities Metro Region, a series of events have catalyzed to make now the time to move forward on regionalization for housing justice. In the last few years, the region built out infrastructure in its efforts to respond to unsheltered homelessness, but the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the cracks and flaws in responses to homelessness that are focused on crisis and shelter rather than preventing homelessness and supplying affordable housing to meet local demand. The murder of George Floyd, and the local and national response to his murder, exposed the racist foundations of many systems purporting to serve people; housing is no exception. Advancing housing justice through regionalization requires that the people living in the Twin Cities Metro Region to stand behind and push for housing justice. The Blueprint reflects a path for getting there.

Racial Equity is not just the absence of overt racial discrimination; it is also the presence of deliberate policies and practices that provide everyone with the support they need to improve the quality of their lives. It is a state in which all people in a given society have equal rights and opportunities. To pursue equity, policies and frameworks for society must address the underlying and systemic differences of opportunity and access to social resources.

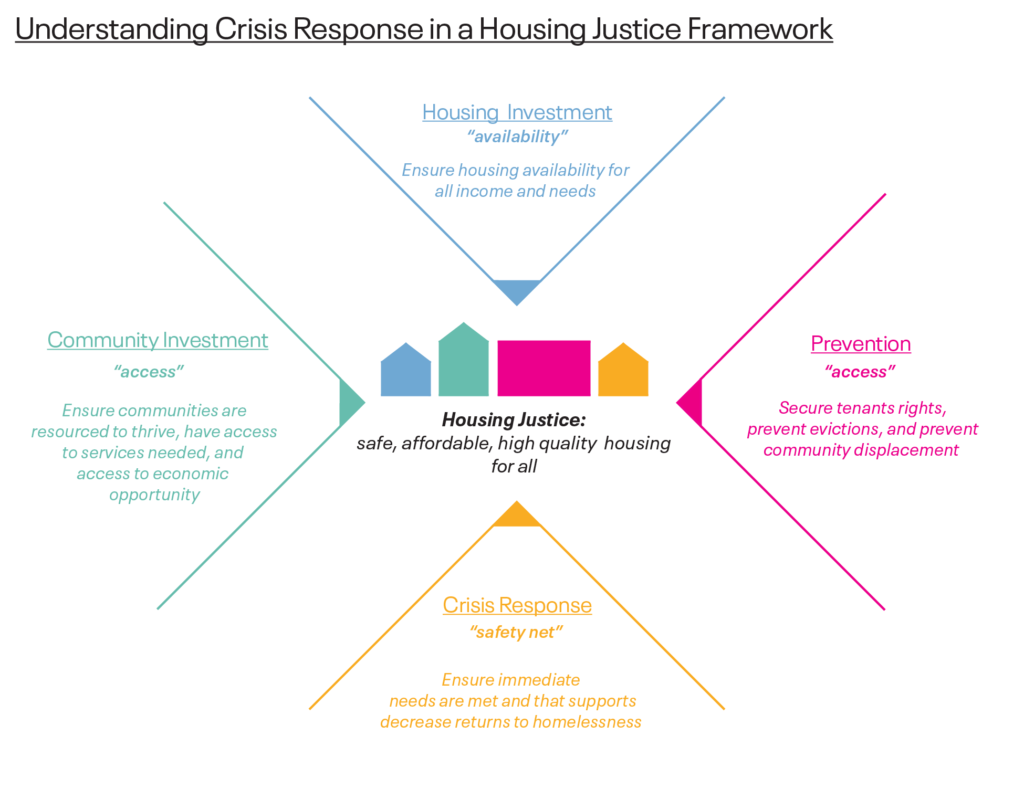

Housing justice for us means guaranteeing opportunities for everyone in our country to have affordable, safe, accessible, stable housing through a racial justice approach.

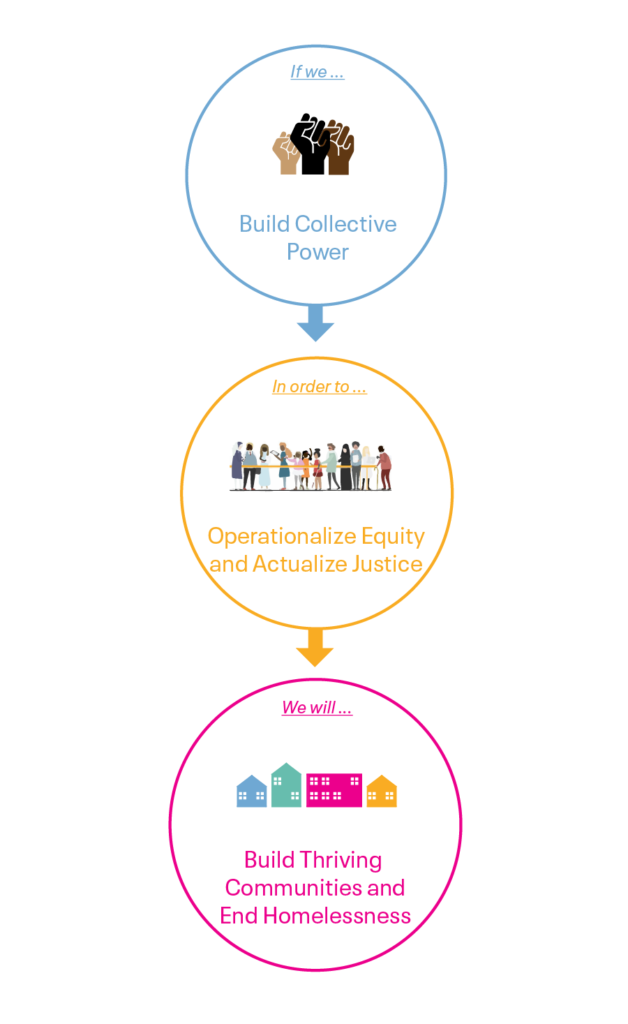

The theory of change for regionalization in the Twin Cities Metro Region is simple: when we focus on building collective power, we can actualize justice, create thriving communities, and end homelessness.

We understand power to be fundamentally rooted in people. When power is redistributed to and spread amongst the people most harmed by systems meant to help them, those systems are actively transformed into ones where every community member doesn’t merely remain housed but thrives as well. System transformation happens by comprehensively redistributing power, resources, and authority.

This kind of system must be approached regionally if we are to comprehensively prevent and end homelessness. The local network and fabric of infrastructure, costs of living, and the interconnectedness and interdependence of people, families, and communities across counties require this regional approach.

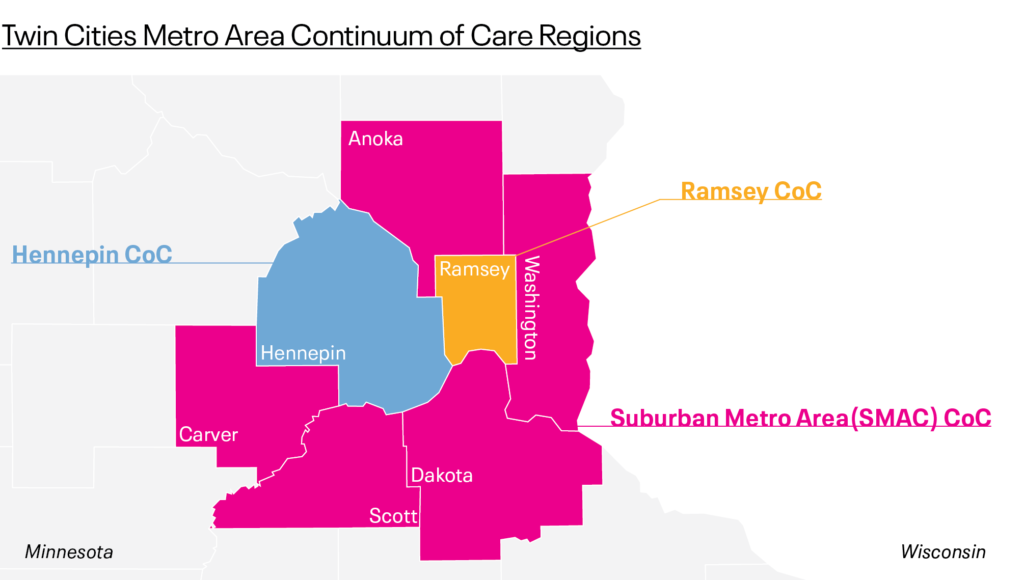

The Regional Blueprint is a strategy framework that indicates a way forward for the region. For the purpose of this Blueprint, the Twin Cities Metro Region is defined as the geographic region that is Anoka, Carver, Dakota, Hennepin, Ramsey, Scott, and Washington counties and includes communities, planning and advocacy bodies and local governments within them. In addition to the geographic reach and current functions of the homeless response system; the effort also included investigating the overlapping roles, jurisdictional authorities, investments, and advocacy of key agents and entities that are currently charged with preventing and ending homelessness in the region.

The COVID-19 pandemic has greatly exacerbated racial inequity and socioeconomic burdens on communities of color and Indigenous communities across the country. Decades of activism among Black, Indigenous and communities of color (BIPOC) have already highlighted these growing and cumulative effects of structural racism. When George Floyd was murdered on May 25, 2020, he became one of the millions whose dreams and lives have been stolen in North America to uphold white supremacy, exposing the transformation necessary not only across the country but very explicitly right here in the Twin Cities Metro Region.

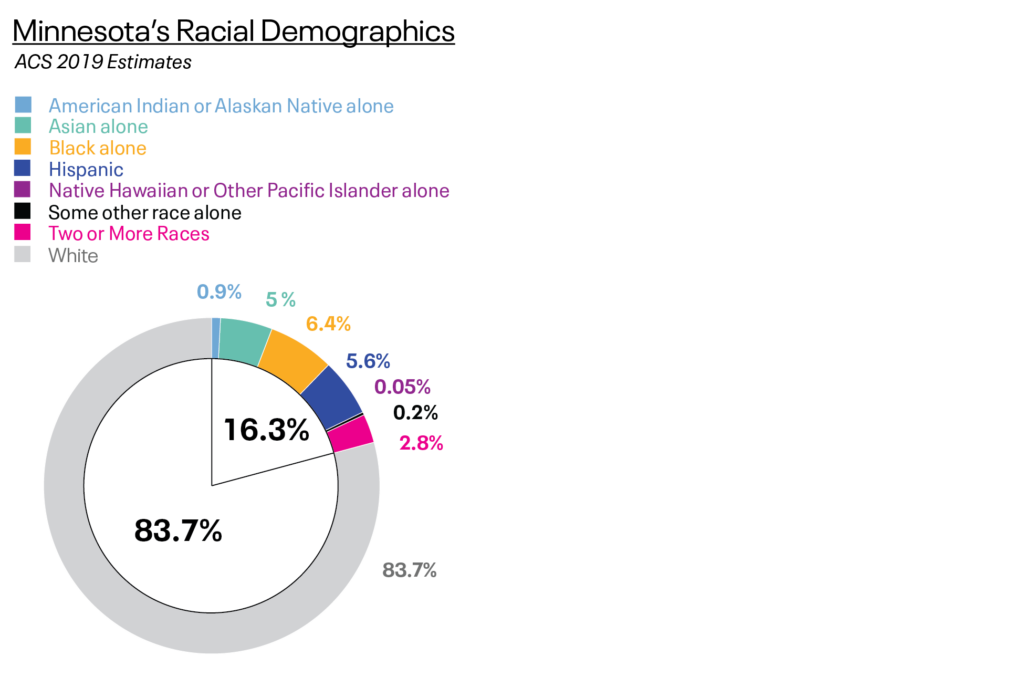

The Minnesota Paradox demonstrates how effective the state’s systems are at perpetuating inequity and inequality. The state’s rates of racial disparities are some of the worst in the nation.

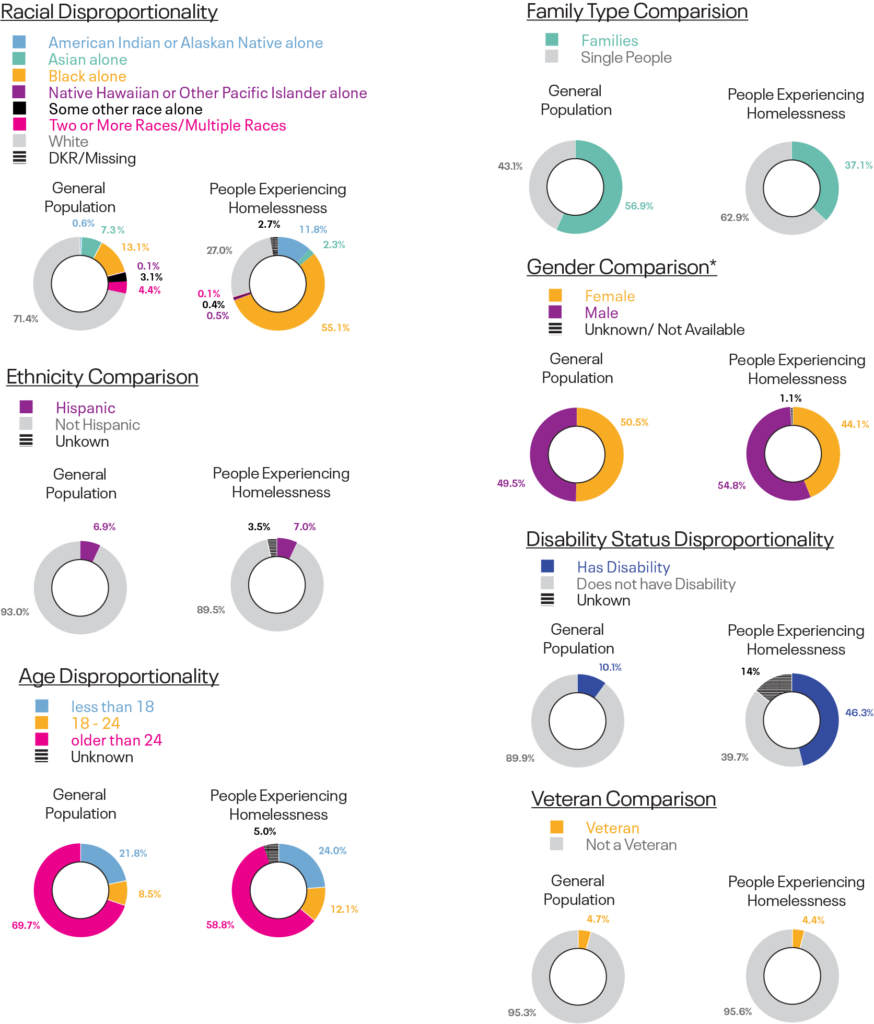

Rates of homelessness, unemployment, maternal mortality, infant mortality, incarceration, arrests, are disproportionately high among Black and Indigenous people in Minnesota while life expectancy, income, wealth, and homeownership rates are lower. These disparities are intentional outcomes of systems built to oppress. Recent research shows that residential segregation even reinforces other disparities, demonstrating the intersecting and compounding effects of these systems of oppression.

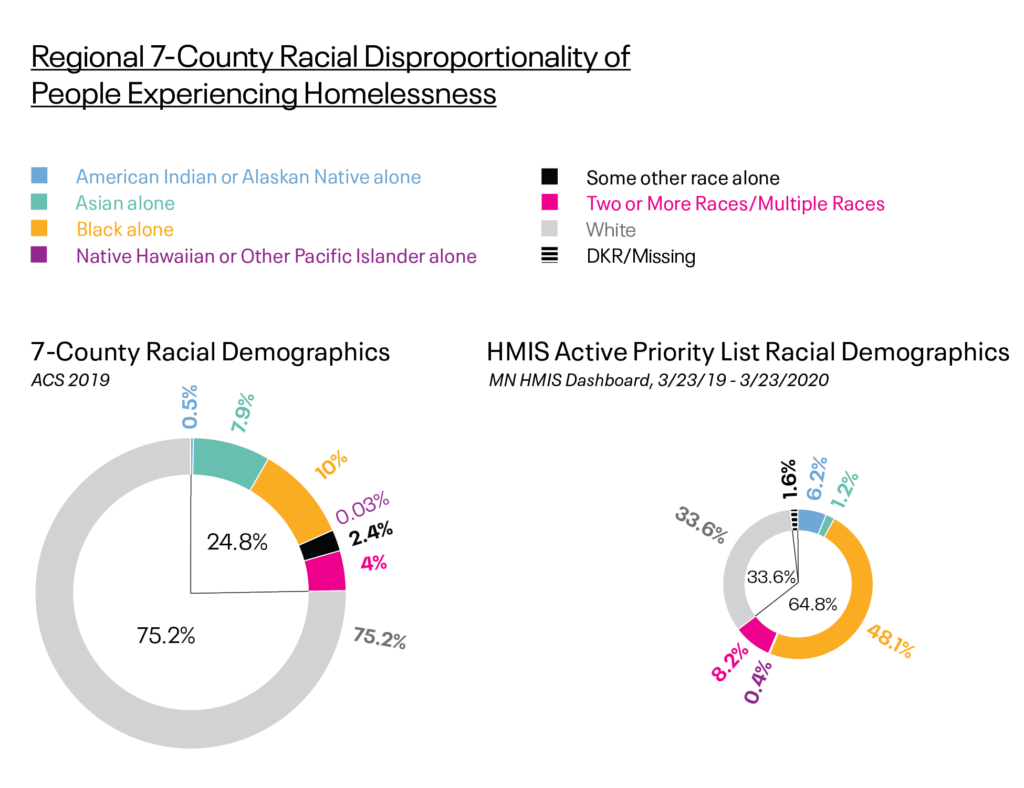

Black and African Americans in Minnesota only make up 7% of the state’s population but accounted for 56% of the people counted as experiencing homelessness in the Twin Cities Metro Region on a single night last year. Indigenous people, defined by the government as Native American and Alaskan Natives, represent 1.4% of the state’s population and yet 6.5% of the people counted on that night in the region were identified as Indigenous.

These alarming data points only scratch the surface. Recent research found that Black and African Americans who are experiencing homelessness in the Suburban Metro Area Continuum of Care (SMAC) are more likely to move into temporary housing or double up with other households after receiving services while others are connected more frequently to permanent housing options and services.

Disproportionate rates of homelessness are the direct product of the last century of housing policy in the region and in the nation more broadly. Before many Black and African American families were planting roots in the region and before the Great Migration, white landowners began laying the groundwork for housing segregation. Law and policy were key tools in achieving this segregation with white landowners using racially restrictive covenants to block Black and African Americans from buying property, policies now considered to be the Jim Crow rules of the North. Segregation did not begin in the Twin Cities region until 1910, when a white resident and property developer wrote the community’s first housing racially restrictive covenant into a deed, paving the way for Black and African Americans in the Twin Cities Metro Region to now have the lowest rates of homeownership in the entire country.

Racially restrictive covenants have evolved. Today, “race-neutral” language stands in place of explicit racism. Barriers to access, convoluted processes and regulations, and overt interpersonal racism prevent BIPOC communities from attaining and sustaining housing stability or having meaningful choice in housing options. In an initial analysis of the data available from 211, HMIS, Wilder Research, and the American Community Survey (ACS) we found:

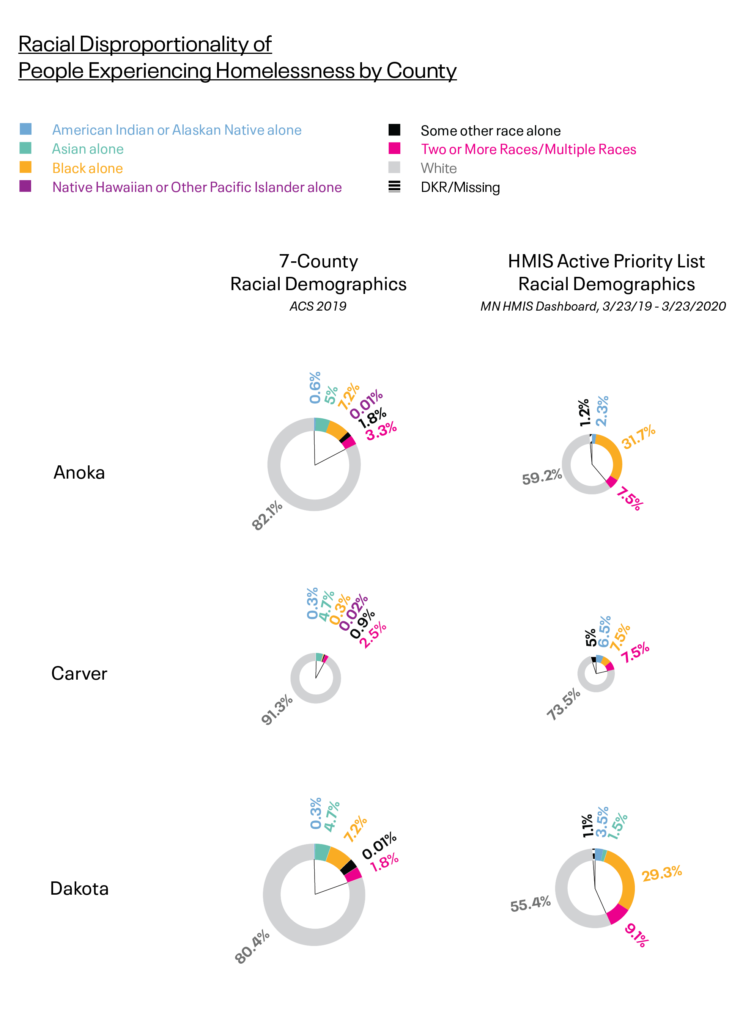

- Native Americans are overrepresented in the population of people experiencing homelessness by a factor of 12, and Native Americans are 26 times more likely to experience homelessness than White people.

- Among the suburbs, Anoka County has the most disproportionate number of Black individuals experiencing homelessness. Hennepin County has the highest rate of disproportionality, followed by Ramsey, then Anoka.

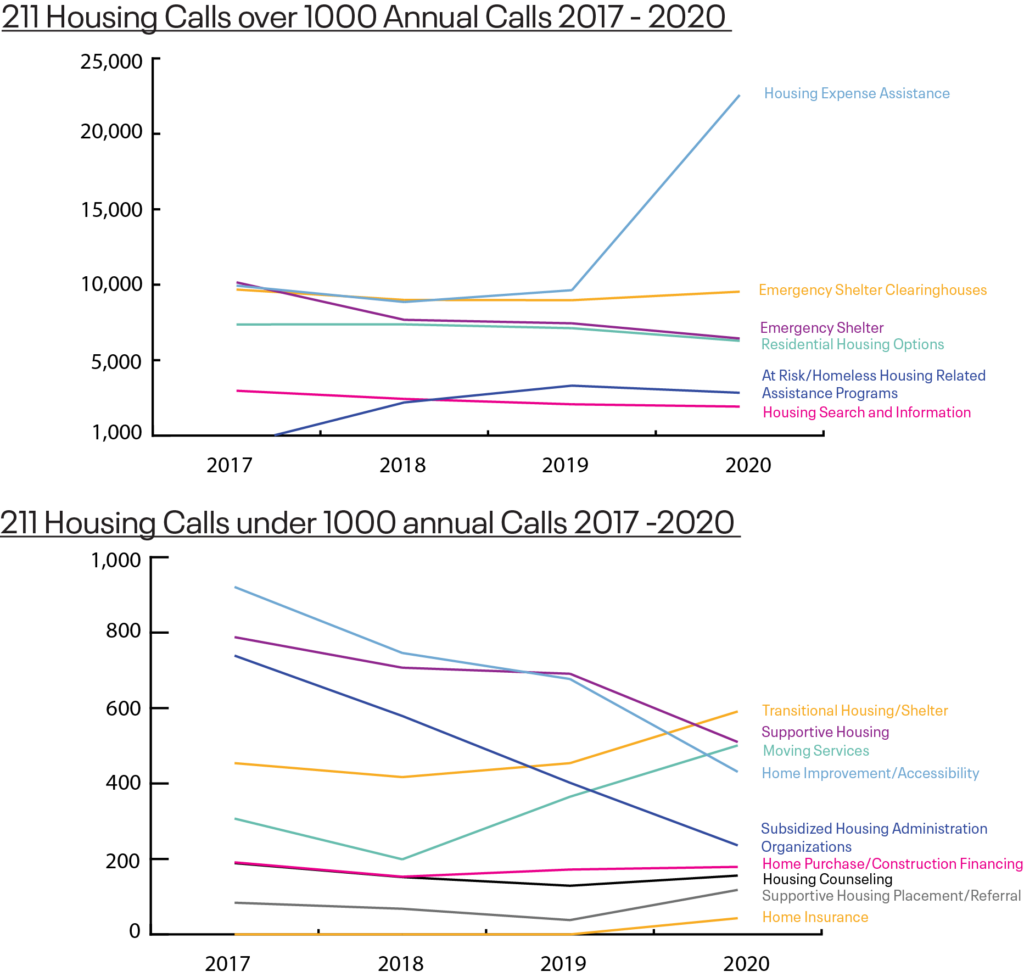

- Anoka County had a higher rate of United Way 211 “First Call for Help” calls based on its population size, even taking its poverty rate into account. Calls coming from Hennepin County were less than proportional to its size in the region, as were calls from Washington, Dakota, and Carver Counties.

- The only counties to report that there are individuals who identify as Asian experiencing homelessness were Dakota (2%), Ramsey (3%), and Hennepin (1%). Homelessness among Asian people seems likely to be undercounted in Hennepin County, while the rate of homelessness among Asian people is higher in Dakota County than in other suburban counties.

Recent efforts have attempted to address these disparities. The Unsheltered Redesign Committee produced an initial framework for a regional approach to respond to the unsheltered population in the Twin Cities Metro Region. Published in February 2019, the Responding Effectively as a Region to Unsheltered Homelessness in the Twin Cities Metro Area Framework introduced key system components, defined the unified governance structure, political will, and public awareness needed to advance a regional approach to unsheltered homelessness. The framework also delivered recommendations and established the Regional Advisory Committee to provide direction, oversight, strategic thinking, and guidance as strategies were implemented across the region, most of which were adapted for and advanced during the COVID pandemic.

As of April 2021, the Regional Advisory Committee celebrated the following accomplishments:

- The creation of over 2,800 temporary shelter options (typically hotel/motel), cover staffing, and provide food and personal protective equipment.

- The creation of ongoing additional emergency shelter capacity for over 300 Minnesotans.

- The innovative use of the Housing Support program to promote COVID-safe congregate settings and implement a hotel-to-home model connecting people staying outdoors with permanent housing.

Despite this work and efforts to adapt to the changing environment in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, housing instability and homelessness are rising in the region for BIPOC individuals and families, as is the case across the country.

The pandemic itself has impacted the capacity of the region to respond to homelessness. It has also created economic instability—due to health and health care challenges as well as due to the profound impacts on employment in the service sector—for even more households, those households are disproportionately BIPOC. The pandemic has exacerbated historical racism embedded in employment systems, as well. Housing insecurity has only increased in the face of these challenges.

When considering the scale of the challenge the pandemic has presented and layering it onto the historical and current patterns of racism in housing, the decades of scaled divestment in housing, and the mounting unaffordability for people with extremely low incomes, the path forward can seem daunting.

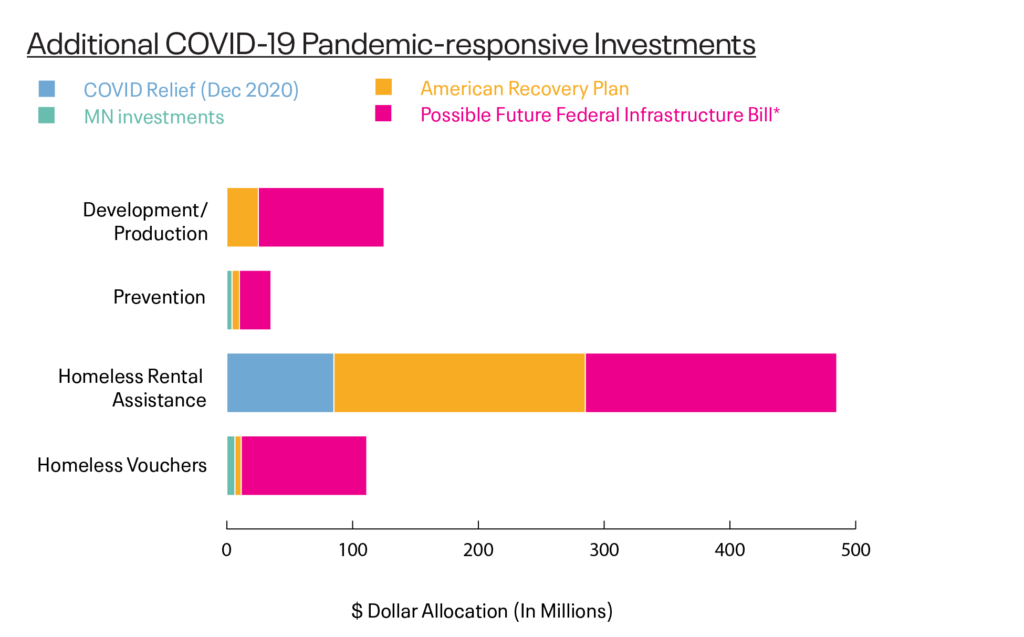

Yet alongside these challenges, the state and the federal government have both allocated historic investments in housing and homeless assistance. There is a new opportunity with funding allocated at scales that have not been imagined in recent history. This funding is aimed at preventing homelessness, providing short-term and long-term rental assistance, and providing capital investments to build the supply of housing at affordable rates.

While the amounts of the investments in the chart above may shift marginally, the truth of the moment holds: there are already significant new housing resources flowing into Minnesota, with more potentially coming in another infrastructure bill currently being negotiated by the federal government, which are reflected in the chart above as possible projections. The scale of these investments will demand new approaches and in some instances the need to re-imagine substantial changes in policy, investments in infrastructure and a change management plan.

The scale of this opportunity offers a catalyzing decision point:

- keep making decisions about resource allocation, spending, and priorities in the ways that fuel the racial disparities and inequities described above; or

- invite a new approach that includes and responds to people who have historically been left at the margins, and understands the nature of the funding decisions as interconnected regionally.

These new and substantial resources provide a platform to consider a Blueprint that addresses the findings discussed in detail below.

Shifting toward housing justice requires centering voices of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) who have experienced the homelessness crisis response system in jurisdictions across the Twin Cities Metro Region; hearing successes and failures of prior efforts from system administrators, and; building a vision together for what would need to change to achieve housing justice for the region. The Center for Housing Justice (CHJ) held those values in a process with three core components: 1) a policy and decision-making audit; 2) community engagement and; 3) building community support. The process (for phase 1) began in December 2020 and will conclude August 2021.

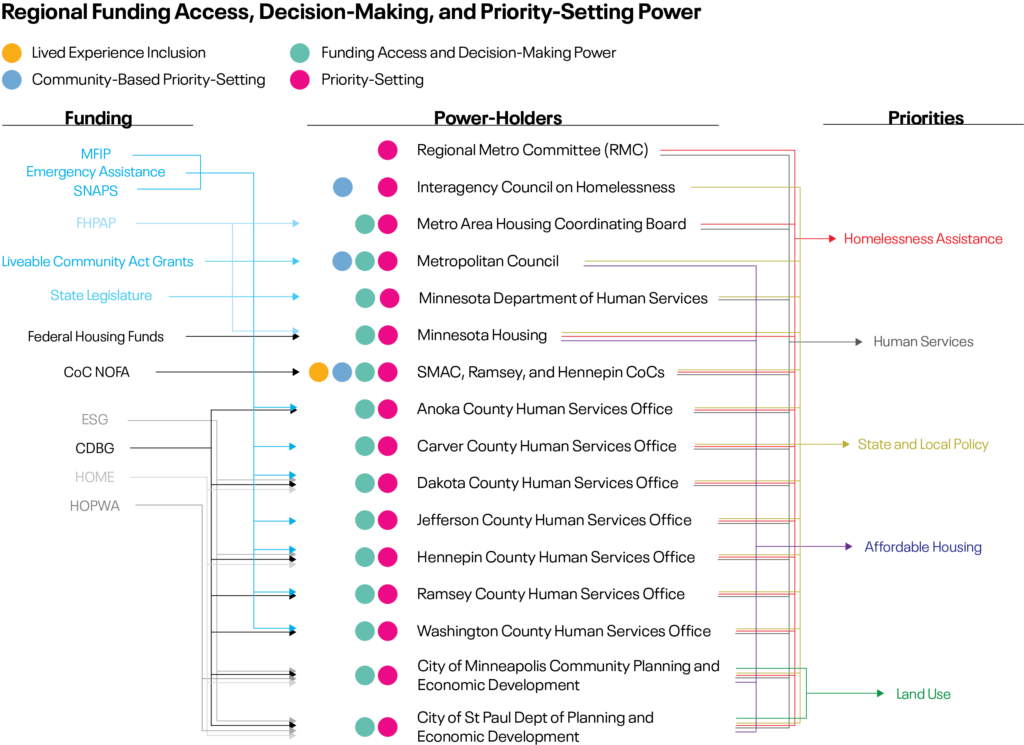

The policy and decision-making audit consisted of a review of regional policy and decision-making drivers, mapping key regional stakeholders, and reviewing related efforts and “calls for action” of organized grassroots movements in the region.

The policy and decision-making driver elements of the audit focused at the state, regional, county, city, and Continuum of Care (CoC) levels. CHJ reviewed previous and existing efforts to institutionalize coordination and funding allocation regionally. At the regional level, CHJ analyzed tools used by the Metropolitan Council, collaborations and negotiations amongst metro cities, and analyzed provider capacity to meet rental assistance and service needs within and across county boundaries. At the county level, CHJ analyzed the cooperative agreement among metro counties to jointly receive and administer grants, the authority of the Housing Coordination Board, and the implications, power, and reach of the County of Financial Responsibility (CFR) requirements. At the CoC level, CHJ focused on the coordinated entry systems across the region.

CHJ also created a regional stakeholder map to identify the formal and informal power structures across the jurisdictions and region when it comes to priority-setting, decision-making, and financial allocations related to housing and homelessness in the region. The map includes statewide and regional governmental entities, organizing and advocacy groups, CoCs, regional collaborations and coordinating bodies, and philanthropic partners.

CHJ conducted a review of grassroots organizing efforts in the region, particularly where there are demands for housing. We conducted a review of materials posted online and conducted outreach to grassroots organizations to gather additional information.

An advisory group was established to partner with the CHJ team in the systems audit as subject matter experts, to inform the audit findings report, and to advise and contribute to the development of the blueprint proposal and coalition in preparation for Phase II.

The Regional Advisory Group consists of 18 members that also represent diverse personal experiences navigating the homeless response system in the seven counties. Members also identified as activists, community organizers, and workers at the front line of homeless services. Advisors represent groups such as the Regional Experts Network (REN) organized by the Minnesota Coalition for the Homeless (MCH); the Director’s Council of the SMAC CoC; community organizing groups like Freedom from the Streets; and youth advocacy groups working to end homelessness and human trafficking.

Through biweekly strategy meetings, community workshops, and stakeholder-specific meetings, members contributed to shaping the audit findings and participated in setting the tone and framing of the report. They will continue to stay engaged in the next phase of the work as possible solutions are proposed to complete the blueprint.

Please note that this document also refers to the Regional Advisory Committee, the advisory body formed in response to the Responding Effectively as a Region to Unsheltered Homelessness in the Twin Cities Metro Area Framework. These two advisory bodies operate independently of each other.

CHJ conducted community engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic, using a host of virtual and online tools to facilitate conversations with key community stakeholders and people who have lived experience of homelessness and housing instability. We talked to people one-on-one in an interview-style format, conducted listening sessions with groups of stakeholders that were pre-organized; arranged focus groups to hear from specific communities, and arranged virtual workshops to digest information and provide feedback in larger group sessions.

CHJ started with a list of recommended system stakeholders from across the Twin Cities Metro Region that originated from current and past efforts, including the regional response to unsheltered homelessness, existing planning bodies that include the Regional Metro Committee (RMC), the Regional Advisory Committee, and the Minnesota Interagency Council on Homelessness. The list included county administrators, leaders in state government, philanthropy, Continuum of Care (CoC), homeless service providers, intermediaries and policy advocacy groups.

Concurrently, CHJ reached out to people not involved in the homelessness systems regionally, but who were key community members. This list included people involved in grassroots organizing and people who have lived experience of homelessness or have sought housing assistance. In both of these groups, we explicitly identified and centered the experiences of Black, Indigenous, and trans* people.

CHJ spoke with system leaders and people with lived experience in each of the seven metro counties through interviews, focus groups, and by joining pre-existing meetings. Once these conversations were completed, CHJ synthesized the information gathered and identified three major barriers to regionalization. The team then conducted five workshops with community members to refine the synthesis.

For true regionalization toward housing justice to be successful, the effort must truly come from the people. CHJ views our role as facilitators of pointed and intentional conversations to identify the most likely paths forward. In this role, we are deeply grateful for the time that the people in the region have taken to engage with us, hold difficult conversations and space, and dream together about a vision for housing that views it as a human right, accessible and available to everyone. The success of regionalization will be entirely based on the ability of varied, diverse, and inclusive groups of community stakeholders leaning into a vision of system transformation that centers power in new ways. Based on our conversations with the people in the metro region, you have expressed unity in such a vision.

While we did reach out to a broad and varied group of community members in conducting the audit; we recognize that time and distance have meant that we did not speak to everyone who could have offered insight into regionalization. We hope that there will be future opportunities to grow and evolve the work as it continues and that those who we were unable to speak with will have future opportunities to engage.

CHJ also recognizes that this engagement took place during the height of the 2020-2021 surges of the COVID-19 pandemic. Pandemic fatigue, grief, and loss have undoubtedly played a role. We have not taken a close look at this role, but feel it in the ways people can show up. Additionally, all of the correspondence CHJ has had with Twin Cities regional stakeholders has been conducted in a virtual environment. The work is both deeply personal and emotional, and the limitations of human interaction via computer and telephone have been deeply felt.

System Materials Audit

Systematic Review of Materials:

- Homeless and Housing Systems

- Unsheltered Design Team Recommendations

- Regional Metro Committee Collaborative Agreement

- Metropolitan Council Housing Policies and Plans

- HUD/Continuum of Care Materials

- Heading Home Equity System Recommendations

- Health and Human Services

- County of Financial Responsibility

- County and City Strategic Plans

- Grassroots Organizing Movement

- A review of drafted demands at the intersection of the people and ideas leading the grassroots movement for black lives and the construct of the current housing systems in the region.

- Regional Models

- All Home Regional Impact Council

- Seattle/King County Regional Authority

- Chicago Metropolitan Area for Planning

- Metropolitan Council

Community Engagement

Participatory research:

- In-depth interviews

- Community Workshops

- Regional Metro Council

- Regional Advisory Committee

- CoCs Leadership Bodies

- Streetworks Outreach Network

- Regional Advisory Group

- Minnesota Interagency Council on Homelessness

- Subject Matter Expert Sessions

- CoC Priorities and Coordinated Entry Systems (CES)

- Metro Housing Coordinating Board

- Regional Advisory Group

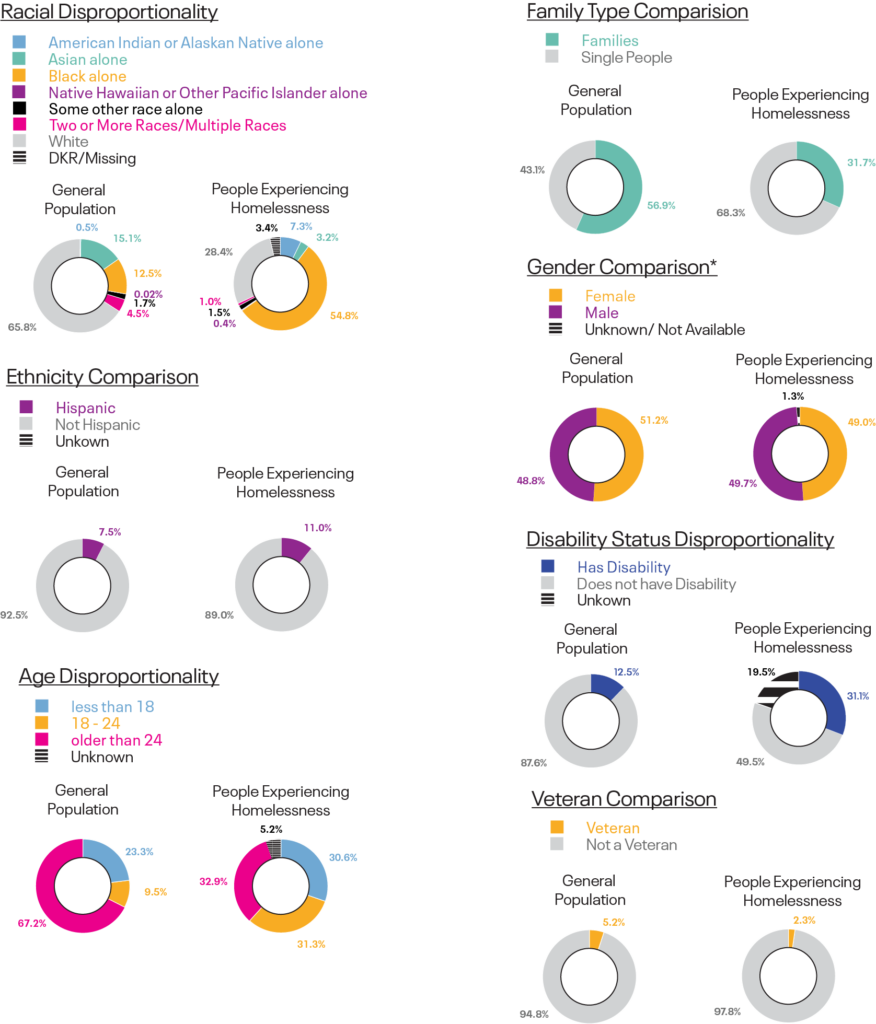

General Population: ACS 2019 Estimates

People Experiencing Homelessness: MN HMIS Dashboard, 2021

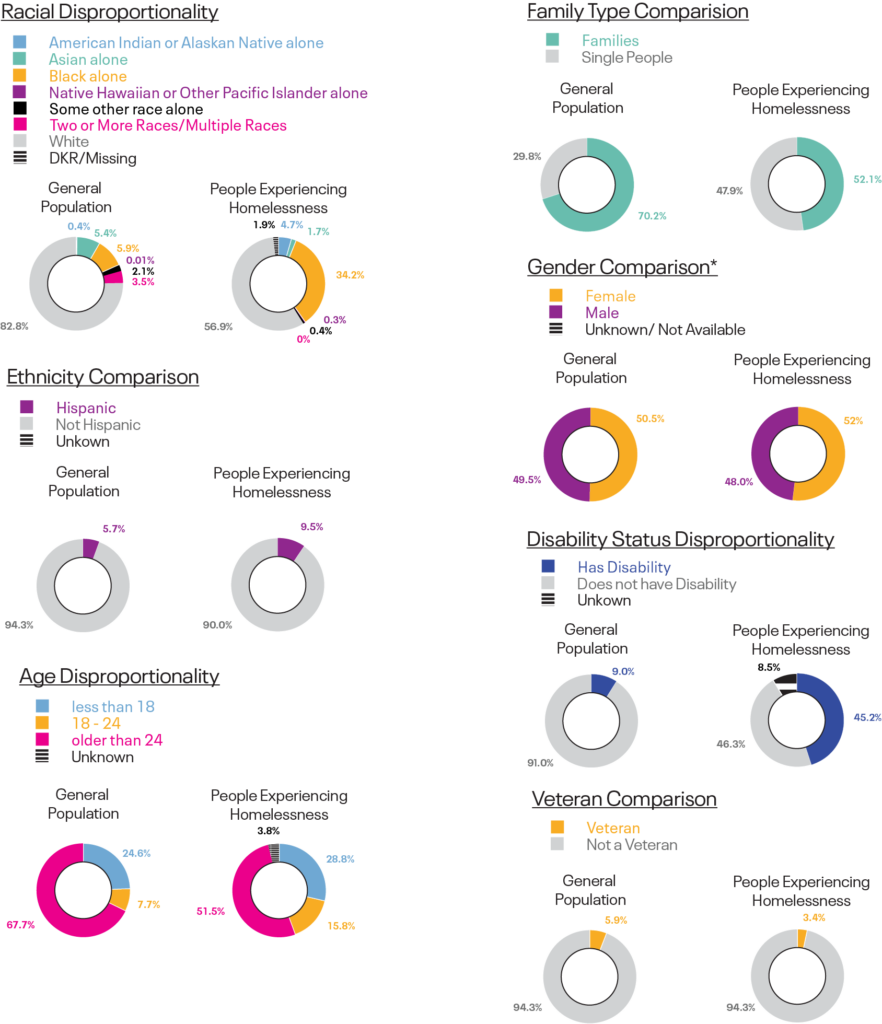

General Population: ACS 2019 Estimates

People Experiencing Homelessness: MN HMIS Dashboard, 2021

General Population: ACS 2019 Estimates

People Experiencing Homelessness: MN HMIS Dashboard, 2021

Minnesota HMIS Dashboard, 2021